Industrial Obelisks: Smokestacks/Barcelona

Versió en català: clica aquí Versión en castellano: clic aquí

As part of the European Union-funded research project PICTURING, Industrial Obelisks is a photography exhibition at The Barcelona History Museum (MUHBA), Oliva Artés. This exhibition uses photography as a tool to reveal spatial processes and social relationships in the city, and to provoke individual reflection and civic dialogue. It aims to stimulate debates about local identity in former industrial neighborhoods, industrial heritage, urban transformation, and the memory politics of redevelopment.

An obelisk is a tall, narrow, tapered pillar, constructed across cultures and geographies since ancient Egyptian times. A form of monument, it is typically erected by the state to glorify a past event, historic figure, or idea. Like other monuments, they have historically served as reminders to a society.

By 1903, art historian Alois Riegl identified the “historic monument” as a monument that was not initially created as such, but that becomes one over time. Architectural historian Françoise Choay has observed that historic monuments have proliferated worldwide since the 1960s. If we accept these premises, nearly any object or structure can go through a cultural process of monumentalization.

Can smokestacks, then, be the obelisks of the postindustrial city? During the Industrial Revolution, brick factory chimneys were called “smoking obelisks” both by poet Charles Baudelaire and architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel, who saw them as sublime icons of newly industrializing urban landscapes. As the most important industrial metropolitan area of the Iberian Peninsula for over two centuries, Barcelona has experienced multiple waves of industrialization. Its factories and port generated immense wealth and intense inequalities.

Phases of Industrial Expansion and Displacement in the History of Barcelona

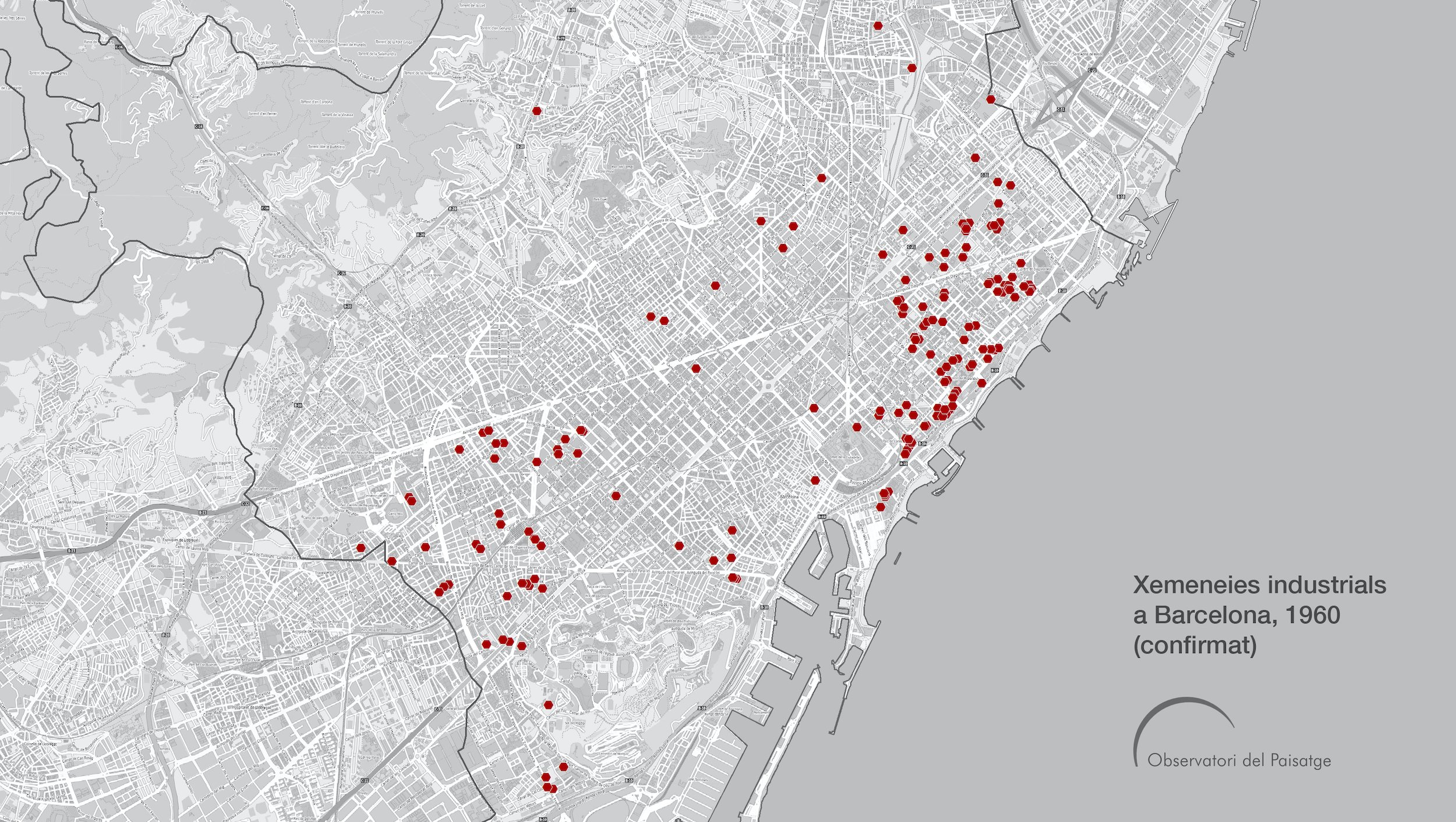

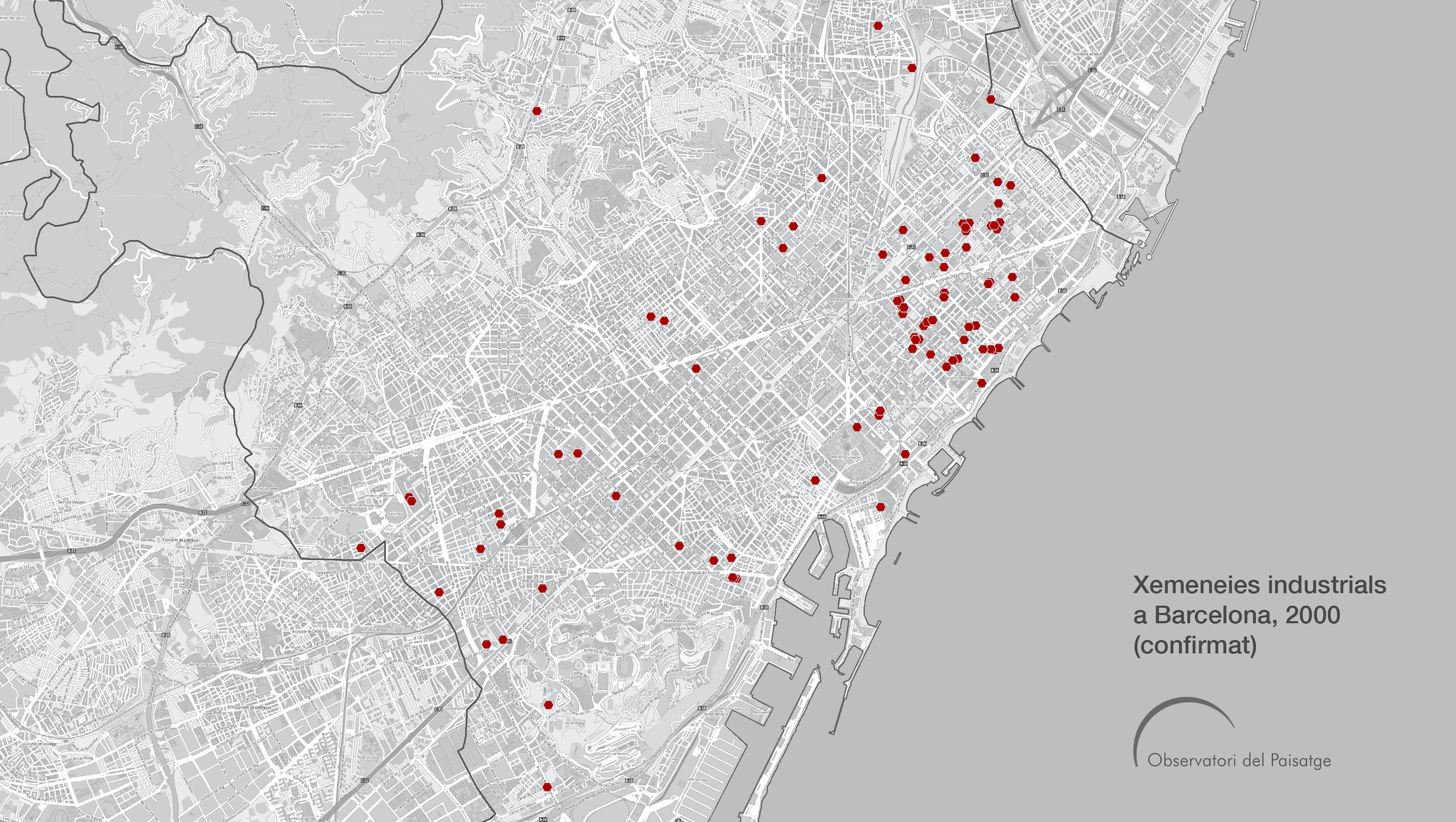

The deindustrialization of the municipality of Barcelona began in the 1960s and coincided with the transition to democracy in 1978. This process was accelerated by international economic factors, new roadway infrastructures, and urban planning policies that pushed manufacturing to the metropolitan periphery. While a great deal of manufacturing has left the city itself, metropolitan Barcelona remains one of the most industrialized areas in Europe.

The displacement of industry is not a new phenomenon in Barcelona’s metropolitan expansion: policies removing manufacturing from the urban core date back to the mid-19th century. Steam-powered textile mills—known colloquially as vapors (literally, steams)—first appeared within the old, walled city (now known as the Ciutat Vella), where 65 were constructed between 1832 and 1848. By 1854, Barcelona was the most densely populated city in Europe. These smoking vapors, along with increasingly insalubrious living conditions, were viewed as threats to safety and public health. This led to a series of regulations limiting the height of chimneys and outlawing construction of steam engines in the Ciutat Vella by 1856. Of the over 300 chimneys that remained in the Ciutat Vella in 1867, only three remain. The demolition of the city walls starting in 1854 led to further industrialization of independent towns on the city’s outskirts such as such as Sants, Gràcia and Sant Andreu, which were then linked together by the Cerdà Plan for the city’s extension from 1860, with the city ultimately annexing these surrounding municipalities in 1897. In this process, Poblenou became the city’s industrial nucleus.

Half of the chimneys in this exhibition are in Poblenou, while most others are located in formerly industrial towns that were gradually absorbed by Barcelona. They were all built between the 1840s and 1950s. Nearly all of them derive from industrial production before the modernization of fossil fuel combustion away from coal-burning steam engines. The earliest chimneys, from the vapors, reflect Catalonia's historic prominence in textile production, while the later ones represent more diversified manufacturing and electricity generation. These technological shifts, along with the relocation of production, made Barcelona’s smokestacks obsolete, even when production continued on the same sites.

Conserving Smokestacks in Barcelona

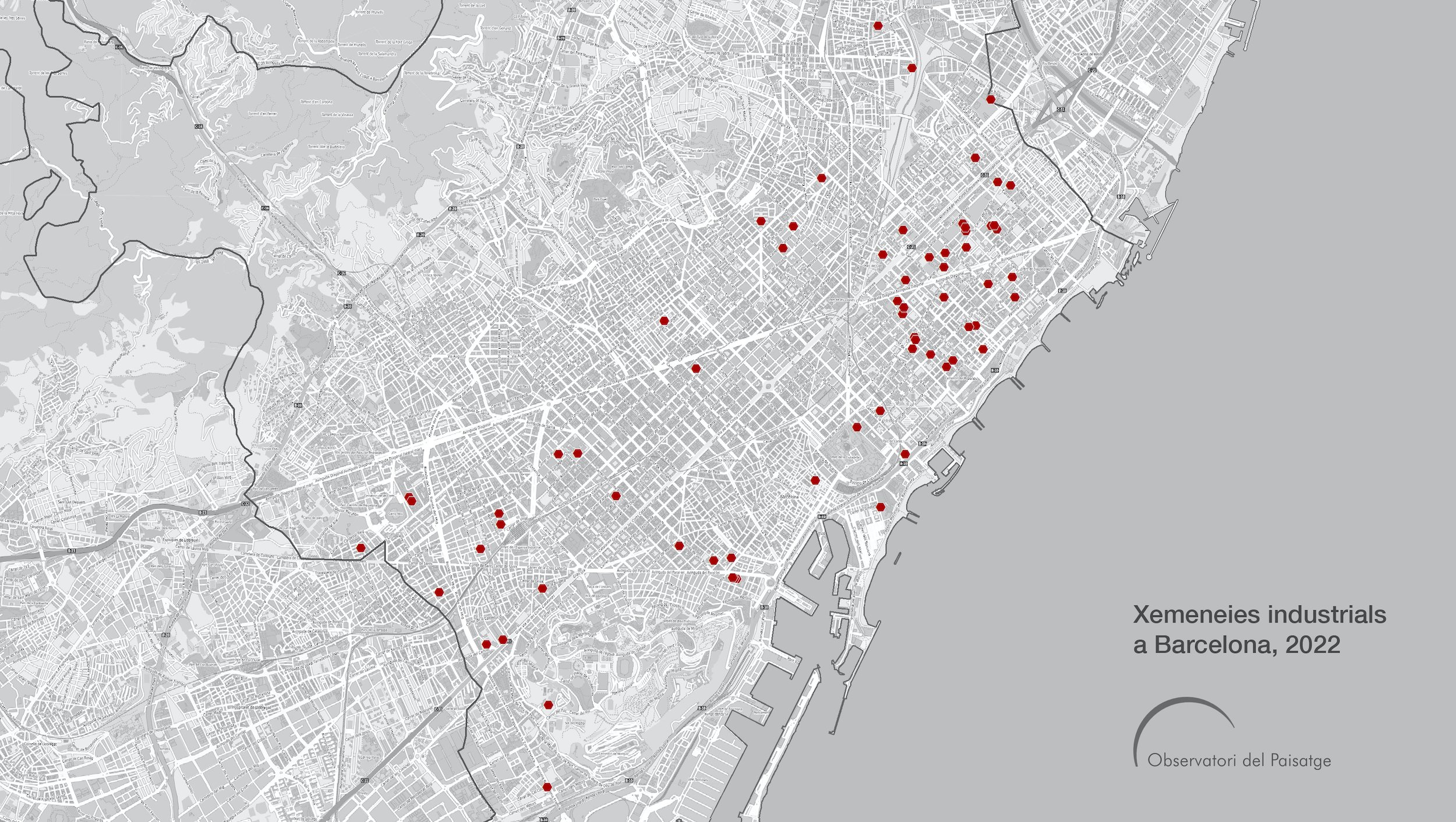

As the above time-lapse map illustrates, many smokestacks have been demolished since the 1960s, after hundreds of others were destroyed in the previous century. Some became industrial ruins, often left standing much longer than the factories they served, due to the cost and complexity of demolition. They were left in states of benign neglect, and occasionally repaired when they represented safety concerns. By the early 1970s, exceptional smokestacks were conserved for their cultural value, such as the Can Batlló textile mill (since 1904 the Escola Industrial) in the Esquerra de l’Eixample, designed by architect Rafael Guastavino in the 1870s.

As a result of the demands of neighborhood social movements and the 1976 General Metropolitan Plan, industrial land began being reclassified and converted into public spaces and facilities. From the 1980s, the conservation of smokestacks became more systematized when they were left as historic monuments in these new parks and plazas: they took on a deliberately symbolic and sculptural role, though the cultural and historic values they embodied remained vague.

In its breadth, the legacy of leaving isolated chimneys as historic monuments is particular to Barcelona, Catalonia, and Spain as a whole: nowhere else has this practice been so widespread. Barcelona’s chimney-monuments became polemicized in the wake of the 1992 Olympic Games. They are seen as symbols of the city’s erasure of physical reminders of its industrial past by critical scholars,[2] local civic organizations,[3] journalists,[4] and heritage practitioners. Often considered a consequence of property speculation, the preservation of these chimneys alone is criticized as a superficial approach to the built heritage. Mobilizations of scholars, industrial heritage activists, and neighborhood organizations resulted in changes in heritage policy that made the practice increasingly less common in Barcelona since the early 2000s. Nevertheless, in 2021, this matter became re-politicized at the level of the Spanish state by the The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (TICCIH): the conservation of solitary chimney-monuments reflects past models of redevelopment, still occurring but less frequently.

Barcelona’s Smokestacks Today

Through photographs and maps, Industrial Obelisks documents 67 remaining smokestacks in Barcelona, mostly conserved as solitary historic monuments. Since 2000, most have been listed as protected monuments in the city´s Catalog of Architectural-Historical Heritage, but this has not always prevented their demolition. Until now an official full inventory has not been undertaken, and since some remain unlisted, there is no sure way to verify the completion of the survey.

In today’s Barcelona, conserved smokestacks occupy constrained spaces on the ground, yet they serve as highly visible landmarks in public spaces and private interior courtyards. Their presence embodies historical compromises between planners, architects, landowners, heritage campaigners, and property developers in an intense real estate market. They tell us about the material presence of the industrial past, but also waves of recent urban transformation.

Nearly all remaining smokestacks in Barcelona have now been rehabilitated and conserved, with property owners typically responsible for their maintenance. Most have legal protections preventing, or discouraging, their demolition. Because of various campaigns spearheaded by heritage activists and neighborhood organizations, the City Hall and local planning bodies (such as 22@) have incrementally expanded their protection of elements of the industrial built heritage, with a shift from focusing on individual monuments (mainly chimneys, but also façades, water towers, etc.) to more complete manufacturing complexes, historic districts and landscapes, in accordance with changing international norms on heritage conservation.

As nearly all of Barcelona’s remaining smokestacks have been conserved, now is an appropriate time to ask: what do these industrial obelisks signify? For example, few have any sort of plaque contextualizing their presence. What do they tell us about the public memory of traditionally industrial, working-class districts, of residents’ and workers’ experiences of deindustrialization, and of processes of urban redevelopment? More broadly, how do they reflect Barcelona’s relation to its industrial past? In a city driven by tourism, how do visitors perceive these historic monuments, and how does that differ from locals’ perceptions across generations and neighborhoods?

Industrial Obelisks depicts Barcelona’s remaining smokestacks as structures within themselves, through their relation to the everyday spaces they occupy, in the context of their surrounding landscapes, and in how the graphic imagery of smokestacks is used in the city. It emphasizes the quantity of these historical monuments remaining in the city, their repetitive yet unique character, and their punctuating effect in a transforming urban landscape.

After viewing the following images, viewers are asked to complete a survey in which they reflect upon their own perspectives and experiences to ascertain what these industrial obelisks signify.

Below: A slideshow of the 67 remaining smokestacks in the city of Barcelona

Having reviewed the images and text from Industrial Obelisks, you are kindly requested to complete this research survey.

If you would like to navigate through a map of chimney locations in Barcelona (and the rest of Catalonia), click the image below. This map is gradually being updated, and if you think anything is missing, please tell me and I will revise it.

Exhibition Credits

Curation, Photography, Text: Brian Rosa.

Exhibition Design: Amica Dall and César Tomé.

Translation: María Aguilar and Albert Fuentes.

Advising: Joan Roca (MUHBA).

Poster Design: Diego Borbalan.

Map Design: Landscape Observatory of Catalonia.

Carpentry: Borja Moreno.

Additional Photography: Joan Bosch.

Additional Support from MUHBA: Marta Iglesias.

With Special thanks to:

Juan Aguilar, Rafael Aguilar, Mari Paz Balibrea, Ethel Baraona, Phil Birge-Liberman, Xavier Boneta, Gemma Bretcha, Juancarlo Castillo, Rosa Cerarols, Helen Cole, Jordi Corominas, Alec Curtis, Marta Dahó, Àngels Dalmases, James Douet, Agus Giralt, Cristina Goberna, Paco González, Marc Guinjoan, Anna Jiménez, Manolo Laguillo, Juan Manuel López, Antoni Luna, Julieta Luna, José Mansilla, Isaac Marrero, Francesc Muñoz, Marianna Nadeu, Josep Niubò, Javier Ortigosa, Jaume Perarnau, Marta Perelló, Emerald Pes, Frank Plant, Xavier Ribas, Genís Ribé, Núria Rius, Roger Roca, Jordi Rogent, Valentín Roma, Amye Rosa, Adam Ryder, Anna Sala, Pere Sala, Carmen Silver, Olga Subirós, Mercè Tatjer, Margarita Triguero, Shanti Vega, Máximo Velasco, Pau Villalonga, Pedro Zambrana.